Outsider at Home With the Inner Life

THE FILMS OF THE Russian director Aleksandr Sokurov, whose ''Mother and Son'' opens on Wednesday at Film Forum, have always demanded a suspension of Western (and particularly American) filmgoing expectations. There will be little dialogue; the plot will neither twist nor turn; editing cuts will be fewer than usual; character development will not ride on a screenwriter's efforts at motivation but will be left largely to the viewer.

The narrative in ''Second Circle'' (1990), for example, is more or less over before it begins. A young man arrives in a desolate, snowy village to bury his estranged father's body; he is often alone on screen with the corpse, with a doctor, a neighbor and undertakers breaking his solitude. Death as a natural part of life is inverted: life seems a part of death. From the standpoint of plot, the film sounds ghoulish, even macabre, but, as executed, it is not; the young man and the corpse are shot at oblique angles, largely in black and white with tones of deep sepia, and what is projected on the screen resembles a film negative.

In 'Mother and Son'' (1997), described by one critic as a ''reverse Pieta,'' a young man cares for his mother as she is about to die. What action there is takes place inside and outside the mother's primitive house in the country; what dialogue there is suggests that their relationship was not easy. The images have a deep, rich texture, as if rendered in the thick, vivid oils of a painting.

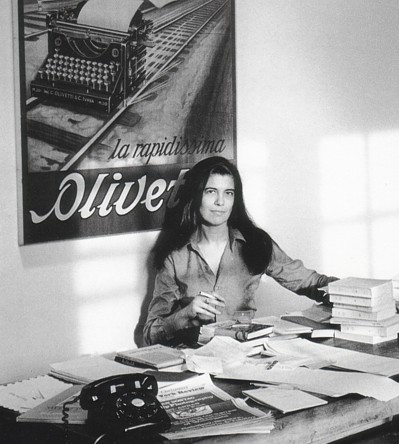

The film's content is comparably rich. The writer Susan Sontag, calling Mr. Sokurov ''perhaps the most ambitious and original serious filmmaker of his generation,'' has noted in particular the ''moral depth'' of his films, which, she says, creates ''an unforgettable emotional experience.'' Because his characters generally lead modest lives, the director can explore large, existentialist themes: love, death, human relationships, man's place in the natural order.

In the program notes for the 20th Moscow International Film Festival, held last July, Mr. Sokurov wrote of ''Mother and Son,'' ''For me it is the love which is important in this relationship -- namely the kind of love which is serene, and does not need to search elsewhere; a love in which two people are very careful about how they treat each other.'' In Moscow, ''Mother and Son'' won the Russian critics' award for best Russian film; it was also shown last year at the Berlin, San Francisco, Telluride and New York film festivals.

SINCE 1978, MR. SOKUROV has made 10 feature films and more than a dozen documentaries (some as short as 10 minutes, one over 4 hours). In many of his feature films he does not use professional actors. In an interview that appeared in the Moscow journal Film Art in 1996, he said he chose people ''with a complex life experience . . . psychophysical peculiarities, financial circumstances, education and self-education, suicidal attempts, sexual problems . . . the essences of human nature.''

Several years before beginning ''Mother and Son,'' for instance, he met Gudrun Geyer, who plays the mother, in Munich, Germany (she works in documentary films). He could not forget her. Aleksei Ananishnov, who portrays the son, is a manager at Pepsi-Cola in St. Petersburg; Mr. Sokurov has known his family for many years.

''For Sokurov, using an actor wouldn't work,'' said Mikhail Iampolski, a friend of the director's and a former researcher with the Institutes of Film Studies and Philosophy in Moscow who is now a professor of comparative literature at New York University. ''The idea of authenticity is extremely important. He takes a prolonged look through the camera; watching an actor for a long time would reveal falsity.''

If a film by Mr. Sokurov yields the unexpected, so too does a conversation with him. In Moscow, shortly after he won the critics' award, he responded to a reporter's question about his next film and new ideas in Russian cinema by cautioning against people who say they have new ideas. ''In art everything is very defined,'' he said. ''Basic artistic tenets were formulated a long time ago.'' They're not old, they're not new; they simply exist, he said.

Mr. Sokurov is in his late 40's and is darkly attractive, with a moody intensity that is held in check by a gracious attentiveness. He answers those questions he deems legitimate and serious -- that is, those about his work -- and politely refuses others he considers personal, all the while clearly showing that he feels there are certain things it is hard for a Westerner to grasp.

He ignores contemporary literature and instead reads Chekhov, Flaubert, Thomas Mann and Faulkner. He calls the lack of a canon in filmmaking ''the first and main vice of the cinema,'' and takes his visual cues from the paintings of Rembrandt, Andrew Wyeth and, in the case of ''Mother and Son,'' Caspar David Friedrich, the 19th-century German Romantic who painted haunting, mystical images of man in nature.

Last September, at the end of the Labor Day weekend, the director was in New York for 23 hours, on his way back to St. Petersburg, where he lives, from Telluride, Colo. He could not return for the New York Film Festival, which was starting several weeks later; his hectic schedule included dinner with Mr. Iampolski, a conversation with the American director Paul Schrader and an interview in a swanky cocktail lounge near Lincoln Center.

In that unlikely spot, Mr. Sokurov spoke about the reception of ''Mother and Son.'' While pleased with such a cordial reception outside Russia, he found it hard to accept that after watching it, people quickly resumed their lives -- going out to dinner, talking, laughing. ''In the West, people don't let themselves be as moved by art,'' he said. ''Russian people allow it all the way into the depths of their soul.''

In Russia, artists have always been considered prophets, and Mr. Sokurov fits squarely into that tradition. ''The purpose of art is to prepare man for the fact of death,'' he said. ''Art gives us many chances to rehearse events of this nature; art is like a coach. Art says that what is most frightening about death is the parting.''

In the interview, the word smireniye came up often. It refers to a state of being that is necessary for the reception of God's grace, a state of acceptance or humility, but one that can be actively reached. ''I would add too that the purpose of art is to make people softer, more moral, fragile and tender,'' he said.

Although he seems most at ease with such weighty discussion, Mr. Sokurov can shift quickly to amusing anecdotes. In looking for financing for ''Mother and Son,'' he said, he went to some Japanese backers; they were excited about the script until they discovered that it was not about incest. A few minutes later, he recounted a story about living in what was then Leningrad in the 1970's and going out each night at 2 A.M. for a walk on Kirovsky Prospect, where workers were diligently painting a huge portrait of Leonid Brezhnev. Recalling that era of stagnation, Mr. Sokurov laughed and said, ''It gave me some stability.''

It is hard for Westerners not to interpret the desolate landscapes and solitary individuals in many of Mr. Sokurov's films as criticism of the Soviet system. In his documentary ''Maria'' (1978), an outspoken peasant on a collective farm has her spirit dampened after quarreling with the authorities; she dies at the age of 45. In ''Days of Eclipse'' (1988), a Russian doctor is sent to an isolated post in Central Asia; each day, he must repeat the same inane phone conversation with the same authority.

Isn't there some political comment about the Soviet days being made in at least some of his films? ''Categorically no,'' said Mr. Sokurov. ''In my art my purpose was not to criticize the system; the particulars are what I knew.''

CRITICS WHO KNOW HIM well agree. ''He's much more involved in metaphysics,'' said Mr. Iampolski.

That does not, however, mean that Mr. Sokurov was not affected by the Soviet system. Although he began making films in the 1970's, his films were not released until glasnost in the mid-1980's. (In 1989, Tass reported that his films had been ''previously regarded by fearful bureaucrats as ''heretical'' and ''abstruse.'')

During his brief stop in New York, Mr. Sokurov also recalled those days with Mr. Schrader (part of their discussion was published in a recent issue of Film Comment). ''I was always driven by visual esthetics, esthetics which connected to the spirituality of man, and set certain morals,'' Mr. Sokurov said. ''The fact that I was involved in the visual side of art made the Government suspicious. The nature of my films was different from others. They didn't actually know what to punish me for -- and that confusion caused them huge irritation.''

Questions of his art are natural for Mr. Sokurov to address; he only alludes to the difficulties that art has created in his life. He said that if he could stop being a filmmaker, he would, but that he can't. A film a year leaves little time for anything else; he leaves home at 8 or 9 in the morning and returns at midnight. Mr. Iampolski recalled many years ago, after he had written a favorable piece about Mr. Sokurov's films in Film Art, he invited the director to Dom Kino, the filmmakers' union headquarters in Leningrad, so that they could meet. Mr. Sokurov accepted but added, ''Where is Dom Kino?''

His outsider status has not really subsided even as his films have become more recognized in international circles. Andrei Tarkovsky, the renowned Russian director who died in 1986, is said to have left Russia to find it. Mr. Sokurov grew up not in Russia but in Siberia, Poland and Turkestan (his father was a professional soldier): although he lives in Russia, he is, in a sense, exiled from the place of his birth.

''I was born in a little village in Siberia that doesn't exist anymore,'' he told Mr. Schrader. ''They built a hydroelectric power station, and my little village was buried under water. If I want to visit the place of my birth, I could take a boat, get there by the water and look into the bottom of the sea.''

| Mother and Son |

| Review by IFQ Critic Todd Konrad |

| Christened by critics as the cinematic and spiritual successor to Andrei Tarkovsky, Russian filmmaker Aleksandr Sokurov indeed proves his worthiness with sublime skill in his film, Mother and Son. Experimental in form and abstract in theme, the film has been praised by various figures, i.e. Susan Sontag, Nick Cave, Paul Schrader, etc. Bold in terms of its directness and unapologetic sentimentality, the film stands as both testaments to Sokurov's directorial skill and to the deeper, primordial themes it explores. Whatever one's final opinion may be of it, Mother and Son is a film unlikely to be easily forgotten by those fortunate and curious enough to take a chance on it. The film begins in an idyllic landscape, seemingly untouched by civilization with the exception of a lone train that travels along in the distance and a small wooden cabin where the aforementioned characters live. The two leads, an ailing mother (played by Gudrun Geyer) and her adult son (played by Aleksei Ananishnov) reside within this small cabin in the middle of this pristine land. It is evident that the mother is on the verge of death, visibly frail and mentally slipping, she attempts to hold onto every last breath and thought she is capable of knowing the fate that draws inevitably closer. Her son attends to her needs dutifully and does all he can to make her final moments easier. Together they engage in oblique conversation, rarely speaking directly of the consequences her death will create. Instead, he tries to bring whatever comforts he can for example taking her for a walk in the countryside to observe the landscape and take in the land and views around them. Despite his good intentions and efforts, the son gradually but painfully accepts his mother's mortality. While he may accept it as an inevitable, natural function, one senses that this does not fully alleviate his pain and heartbreak. Indeed, when the moment finally comes, the only comfort he has is his knowledge that in time, he inevitably shall share his mother's fate and in that moment perhaps they will be reunited in a better world. As the film's relatively basic narrative draws to a close, one cannot help but feel the basic emotional connection to these two characters. The beauty of Sokurov's tale is that its characters are so basic that one can substitute themselves and their family into it with little ease. The mother and son are not fully formed individuals but rather abstract representations; they are every mother and every son. As such, they are utilized by Sokurov in an attempt to create as strong and direct an emotional connection as possible with the viewer. The film does not attempt to create any overly intellectual constructs to ponder over, it is concerned with striking at the viewer's heart rather than mind. It is in this aspect, that Sokurov can truly be seen as Tarkovsky's successor in his boldness to connect to the viewer's emotions as directly yet honestly as possible. When watching this film, one would be foolish to overlook the pure visual beauty itself. Using an assortment of techniques and an unbelievably pristine countryside, Mother and Son contains some of the most lyric and painterly images ever committed to film. Comparisons to other visual feasts like Days of Heaven bear little weight as the film surely surpasses all competition in this regard. The film feels and looks as though it were shot in some heavenly otherworld, unavailable for mere humans to tread upon. Yet the employ of such beauty juxtaposed against such weighty themes as mortality enriches the final work with a complexity that other visual candy seen today is unable of achieving. In the end, the film feels as though they are watching a true dream unfold before their eyes. As cinematic trends come and go, it is refreshing to know that such works of pure visual and emotional art are still being produced; films that because of their timelessness will exist with as much power years from now as they did when first projected upon the movie screen. As close as cinema can come to true spirituality, Mother and Son ultimately is not meant to merely entertain but enrich the soul and this is what finally elevates it to art. |

3 p.m. tomorrow; Alice Tully Hall

The predictably unreliable Russian filmmaker Alexander Sokurov has shot this wonderfully eccentric and fascinating film about the last days of Emperor Hirohito's reign as if it were a science-fiction film. And indeed, the otherworldly Hirohito (Issey Ogata) certainly does suggest a somewhat less cuddlesome E.T., both in his alienation from the quotidian world (the coddled emperor can barely dress himself) and in his relationship with his nominally more human protector, in this case General MacArthur (Robert Dawson).

Shot in 35 millimeter in the filmmaker's preferred brackish tones, ''The Sun'' traces Hirohito as he wanders about his compound engaged in meaningless rituals and surrounded by minders who are as much his guards as his servants. In one of the most revelatory scenes, Hirohito, an amateur scientist, dons a white lab coat to examine the pickled remains of a hermit crab. As he waxes poetic about this pathetic pale specimen, there can be no doubt that the emperor -- an all-too-human man raised as a god -- is effectively staring into a mirror. Mr. Ogata, whose mouth incessantly opens and shuts as if the emperor were nothing more than a very costly pet carp, is mesmerizing.

This is the third in a trilogy of films about dictators by Mr. Sokurov, who remains best known here for the technological marvel ''Russian Ark.'' More approachable and certainly far more enjoyable than the first films in the trilogy, ''Moloch'' (about Hitler) and ''Taurus'' (Lenin), ''The Sun'' envisions Hirohito as somewhat of a victim of history without ever suggesting that the emperor should be excused for the role he played in the tragedy of war. This take may not sit well with historians or the literal-minded, but as a portrait of pathology -- that of Japan and of Hirohito both -- it's terrific. As of yesterday ''The Sun'' did not have American distribution and tickets for the one public screening were available. MANOHLA DARGIS

FILM REVIEW; Ties That Bind a Family, Etched in an Orange Light

''Father and Son,'' the new film by Alexander Sokurov, is like a dream within a dream. Its images and emotions are vivid, disquieting and also hermetic, and while it may frustrate your desire for clear storytelling and psychological transparency, it has an intensity that surpasses understanding. Mr. Sokurov, best known to American audiences for ''Russian Ark,'' his 90-minute, single-take digital video tour of the Hermitage, is a film poet whose deepest intentions risk being lost in translation.

This is less a matter of language than of sensibility (though the dialogue in ''Father and Son,'' as rendered in the subtitles, is frequently elusive or abstract). Some of Mr. Sokurov's movies, like ''Russian Ark'' and ''Taurus,'' which is about the death of Lenin, are steeped in the particulars of Russian history, and though the concerns of ''Father and Son'' are domestic rather than social or political, it nonetheless feels, like the films of Tarkovsky or the music of Shostakovich, irreducibly, even confoundingly Russian in its enigmatic soulfulness.

The title characters, played by Andrey Schetinin and Aleksey Neymyshev, live in an apartment in an unidentified seaside city, where the radio plays only Tchaikovsky. The father (Mr. Schetinin), a widower, is a retired soldier, and his son (Mr. Neymyshev), who looks to be in his late teens, is a cadet at a local military school. They rarely wear shirts at home, and their interactions combine preening, competitive display with easy solicitude.

Their relationship is inflected with a virile tenderness that makes them seem more like comrades or lovers than parent and child. The first scene, in which the father comforts his nearly naked son through a nightmare, is filmed with deliberate eroticism, their muscular bodies bathed in orange-tinted afternoon sunlight. This light, which floods their apartment and hazes over the camera lens, is the film's most remarkable feature; at times it seems almost to be Mr. Sokurov's real subject, the function of the characters being simply to reflect and absorb it.

The lighting and Mr. Sokurov's slow, sighing camera movements create a disquieting atmosphere of sensuality. ''Father and Son,'' which opens today in Manhattan, is the middle film in a projected trilogy -- the first installment was ''Mother and Son,'' and the last will be ''Two Brothers and a Sister'' -- exploring the nature of familial love.

The bond between the main characters is tested by what would be, in a more straightforwardly melodramatic film, the usual intrusions and disruptions: the father's grief; the boy's desire for the companionship of his peers; the mysterious allure of women. Even when the events are puzzling and opaque, the feelings in play are sure to be familiar: a parent's desperate identification with his child, and the child's guilty, fierce desire for an independent identity.

''A father's love crucifies,'' the son remarks at one point, ''and a loyal son accepts crucifixion.'' Later, in a rare moment of anger, the father quotes King Lear: ''Nothing will come of nothing.'' Though I hesitate to disturb the ravishing hermeticism of Mr. Sokurov's film by interpreting it, it seems to me that he invokes these cruel, canonical visions of paternity to contest them. In the literature of the West, fathers and sons push one another toward tragedy. In its place, ''Father and Son'' offers romance.

FATHER AND SON

Directed by Alexander Sokurov; written (in Russian, with English subtitles) by Serguey Potepalov; director of photography, Alexander Burov; edited by Sergey Ivanov; music by Andrey Sigle, based on themes by Tchaikovsky; art director, Natalya Kochergina; produced by Thomas Kufus; released by Wellspring. At the Cinema Village, 22 East 12th Street, Greenwich Village. Running time: 84 minutes. This film is not rated.

WITH: Andrey Schetinin (Father), Aleksey Neymyshev (Son), Alexander Razbash (Sasha), Fedor Lavrov (Fedor) and Marina Zasukhina (Girl).

''Russian Ark'' is a magnificent conjuring act, an eerie historical mirage evoked in a single sweeping wave of the hand by Alexander Sokurov. The 96-minute film, shot in high-definition video in the Hermitage at St. Petersburg, consists of one continuous, uninterrupted take. Thanks to recent technological innovation, it is the longest unbroken shot in the history of film. As the Steadicam operated by Tilman Büttner (the German cinematographer of ''Run Lola Run'') floats through the museum's galleries and rooms, a cast of 2,000 actors and extras act out random, whimsical moments of Russian imperial history that dissolve into one other like chapters of a dream.

Mr. Sokurov, who has always been drawn to historical subjects, has said that he wanted to capture ''the flow of time'' in a pure cinematic language that suggests ''a single breath.'' And that's what ''Russian Ark'' accomplishes as it drops in on Russian monarchs from Peter the Great to Nicholas II and catches them living their lives unaware that they're being observed. These keyhole flashes from the past evoke a sense of history that is at once intimate and distanced, and ultimately sad: so much life, so much beauty, swallowed in the mists of time.

''Russian Ark'' is a ghost story set in the Hermitage, the museum that is the pride of St. Petersburg and the repository -- the ark, if you will -- of more Russian history and culture than any other place. Among its components are the Winter Palace (the former residence of the Russian czars) and sections devoted to Russian history and to the life and work of Alexander Pushkin. It also houses more than three million artifacts, including world-class collections of painting, sculptures, prints, drawings and archaeological finds.

The film is narrated in a thoughtful murmur by a contemporary artist who awakens to find himself lost in the 1800's amid a jostling crowd pouring through a side entrance of the Hermitage. As he follows the flow, he catches sight of another out-of-place figure, the Marquis (Sergey Dreiden), a frizzy-haired 19th-century French diplomat dressed in black and the only person to acknowledge his presence. As the two strays wander through the galleries, they carry on a sporadic dialogue in which the Frenchman continually snipes at Russian culture for being pretentious, overly theatrical and more imitative of Europe than truly European.

Along the way they chance on upon Peter the Great beating one of his generals, and Catherine the Great breaking away from a rehearsal of her own play to search frantically for a place to relieve herself. The Marquis encounters the present-day director of the museum, Mikhail Piotrovsky, and complains to him about the odor of formaldehyde. The Marquis, who has an uncanny sense of smell, also enjoys pressing his nose to an epic canvas to savor the smell of pigment. Later, he is shown around a gallery by a blind ''angel'' who discourses on the iconography of a Van Dyck painting and on the artist's relationship with Rubens.

In another, darker time warp, the Marquis strays through the wrong door and finds himself in a chilly outdoor workshop amid drifting snow, and listens dumbfounded to a description of 20th-century horrors that have yet to take place. The companions stray into an interminable ceremony in which the grandson of the Persian Shah, flanked by emissaries, formally apologizes to Nicholas I for the murder of Russian diplomats in Tehran.

The movie, which the New York Film Festival is showing this afternoon at Alice Tully Hall (it is to open commercially in December), culminates in what may well be the ne plus ultra of period cinematic pomp: a re-creation of the last great royal ball held at the Hermitage under Czar Nicholas II in 1913, shortly before the Bolshevik revolution. To the strains of Glinka, hundreds of glitteringly attired courtiers dance the mazurka to a live symphony orchestra (conducted by Valery Gergiev), then make their way down the grand staircase. By this time, the Marquis's snobbery has dissipated, and when the time comes to leave, he is so enchanted that he chooses to remain in this opulent dreamland.

This ultimate display of wealth and privilege is so heady it would be easy to infer that Mr. Sokurov harbors a lingering nostalgia for the pre-revolutionary era of czars and serfs. But this extraordinary sequence even more powerfully evokes the historical blindness of an entitled elite blissfully oblivious to the fact that it is standing in quicksand that is about to give.

RUSSIAN ARK

Directed by Alexander Sokurov; written (in Russian, with English subtitles) by Anatoly Nikiforov and Mr. Sokurov; director of photography, Tilman Büttner; music by Sergey Yevtuschenko; production designers, Yelena Zhukova and Natalia Kochergina; produced by Andrey Deryabin, Jens Meurer and Karsten Stöter; released by Wellspring. Running time: 96 minutes. This film is not rated. Shown with a 15-minute short, Michael Bates's ''Projectionist'' today at 3 p.m. at Alice Tully Hall, 165 West 65th Street, Lincoln Center, as part of the 40th New York Film Festival.

WITH: Sergey Dreiden (the Marquis), Maria Kuznetsova (Catherine the Great), Leonid Mozgovoy (the Spy), Mikhail Piotrovsky (himself) and David Giorgobiani (Orbeli).

Review/Film; Harsh Family Business In a Haunting Siberia

Regarding the Torture of Others

I.

For a long time -- at least six decades -- photographs have laid down the tracks of how important conflicts are judged and remembered. The Western memory museum is now mostly a visual one. Photographs have an insuperable power to determine what we recall of events, and it now seems probable that the defining association of people everywhere with the war that the United States launched pre-emptively in Iraq last year will be photographs of the torture of Iraqi prisoners by Americans in the most infamous of Saddam Hussein's prisons, Abu Ghraib.

The Bush administration and its defenders have chiefly sought to limit a public-relations disaster -- the dissemination of the photographs -- rather than deal with the complex crimes of leadership and of policy revealed by the pictures. There was, first of all, the displacement of the reality onto the photographs themselves. The administration's initial response was to say that the president was shocked and disgusted by the photographs -- as if the fault or horror lay in the images, not in what they depict. There was also the avoidance of the word ''torture.'' The prisoners had possibly been the objects of ''abuse,'' eventually of ''humiliation'' -- that was the most to be admitted. ''My impression is that what has been charged thus far is abuse, which I believe technically is different from torture,'' Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said at a press conference. ''And therefore I'm not going to address the 'torture' word.''

Words alter, words add, words subtract. It was the strenuous avoidance of the word ''genocide'' while some 800,000 Tutsis in Rwanda were being slaughtered, over a few weeks' time, by their Hutu neighbors 10 years ago that indicated the American government had no intention of doing anything. To refuse to call what took place in Abu Ghraib -- and what has taken place elsewhere in Iraq and in Afghanistan and at Guantanamo Bay -- by its true name, torture, is as outrageous as the refusal to call the Rwandan genocide a genocide. Here is one of the definitions of torture contained in a convention to which the United States is a signatory: '' any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession.'' (The definition comes from the 1984 Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Similar definitions have existed for some time in customary law and in treaties, starting with Article 3 -- common to the four Geneva conventions of 1949 -- and many recent human rights conventions.) The 1984 convention declares, '' No exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture.'' And all covenants on torture specify that it includes treatment intended to humiliate the victim, like leaving prisoners naked in cells and corridors.

Whatever actions this administration undertakes to limit the damage of the widening revelations of the torture of prisoners in Abu Ghraib and elsewhere -- trials, courts-martial, dishonorable discharges, resignation of senior military figures and responsible administration officials and substantial compensation to the victims -- it is probable that the ''torture'' word will continue to be banned. To acknowledge that Americans torture their prisoners would contradict everything this administration has invited the public to believe about the virtue of American intentions and America's right, flowing from that virtue, to undertake unilateral action on the world stage.

Even when the president was finally compelled, as the damage to America's reputation everywhere in the world widened and deepened, to use the ''sorry'' word, the focus of regret still seemed the damage to America's claim to moral superiority. Yes, President Bush said in Washington on May 6, standing alongside King Abdullah II of Jordan, he was ''sorry for the humiliation suffered by the Iraqi prisoners and the humiliation suffered by their families.'' But, he went on, he was ''equally sorry that people seeing these pictures didn't understand the true nature and heart of America.''

To have the American effort in Iraq summed up by these images must seem, to those who saw some justification in a war that did overthrow one of the monster tyrants of modern times, ''unfair.'' A war, an occupation, is inevitably a huge tapestry of actions. What makes some actions representative and others not? The issue is not whether the torture was done by individuals ( i.e., ''not by everybody'') -- but whether it was systematic. Authorized. Condoned. All acts are done by individuals. The issue is not whether a majority or a minority of Americans performs such acts but whether the nature of the policies prosecuted by this administration and the hierarchies deployed to carry them out makes such acts likely.

II.

Considered in this light, the photographs are us. That is, they are representative of the fundamental corruptions of any foreign occupation together with the Bush adminstration's distinctive policies. The Belgians in the Congo, the French in Algeria, practiced torture and sexual humiliation on despised recalcitrant natives. Add to this generic corruption the mystifying, near-total unpreparedness of the American rulers of Iraq to deal with the complex realities of the country after its ''liberation.'' And add to that the overarching, distinctive doctrines of the Bush administration, namely that the United States has embarked on an endless war and that those detained in this war are, if the president so decides, ''unlawful combatants'' -- a policy enunciated by Donald Rumsfeld for Taliban and Qaeda prisoners as early as January 2002 -- and thus, as Rumsfeld said, ''technically'' they ''do not have any rights under the Geneva Convention,'' and you have a perfect recipe for the cruelties and crimes committed against the thousands incarcerated without charges or access to lawyers in American-run prisons that have been set up since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

So, then, is the real issue not the photographs themselves but what the photographs reveal to have happened to ''suspects'' in American custody? No: the horror of what is shown in the photographs cannot be separated from the horror that the photographs were taken -- with the perpetrators posing, gloating, over their helpless captives. German soldiers in the Second World War took photographs of the atrocities they were committing in Poland and Russia, but snapshots in which the executioners placed themselves among their victims are exceedingly rare, as may be seen in a book just published, ''Photographing the Holocaust,'' by Janina Struk. If there is something comparable to what these pictures show it would be some of the photographs of black victims of lynching taken between the 1880's and 1930's, which show Americans grinning beneath the naked mutilated body of a black man or woman hanging behind them from a tree. The lynching photographs were souvenirs of a collective action whose participants felt perfectly justified in what they had done. So are the pictures from Abu Ghraib.

The lynching pictures were in the nature of photographs as trophies -- taken by a photographer in order to be collected, stored in albums, displayed. The pictures taken by American soldiers in Abu Ghraib, however, reflect a shift in the use made of pictures -- less objects to be saved than messages to be disseminated, circulated. A digital camera is a common possession among soldiers. Where once photographing war was the province of photojournalists, now the soldiers themselves are all photographers -- recording their war, their fun, their observations of what they find picturesque, their atrocities -- and swapping images among themselves and e-mailing them around the globe.

There is more and more recording of what people do, by themselves. At least or especially in America, Andy Warhol's ideal of filming real events in real time -- life isn't edited, why should its record be edited? -- has become a norm for countless Webcasts, in which people record their day, each in his or her own reality show. Here I am -- waking and yawning and stretching, brushing my teeth, making breakfast, getting the kids off to school. People record all aspects of their lives, store them in computer files and send the files around. Family life goes with the recording of family life -- even when, or especially when, the family is in the throes of crisis and disgrace. Surely the dedicated, incessant home-videoing of one another, in conversation and monologue, over many years was the most astonishing material in ''Capturing the Friedmans,'' the recent documentary by Andrew Jarecki about a Long Island family embroiled in pedophilia charges.

An erotic life is, for more and more people, that whither can be captured in digital photographs and on video. And perhaps the torture is more attractive, as something to record, when it has a sexual component. It is surely revealing, as more Abu Ghraib photographs enter public view, that torture photographs are interleaved with pornographic images of American soldiers having sex with one another. In fact, most of the torture photographs have a sexual theme, as in those showing the coercing of prisoners to perform, or simulate, sexual acts among themselves. One exception, already canonical, is the photograph of the man made to stand on a box, hooded and sprouting wires, reportedly told he would be electrocuted if he fell off. Yet pictures of prisoners bound in painful positions, or made to stand with outstretched arms, are infrequent. That they count as torture cannot be doubted. You have only to look at the terror on the victim's face, although such ''stress'' fell within the Pentagon's limits of the acceptable. But most of the pictures seem part of a larger confluence of torture and pornography: a young woman leading a naked man around on a leash is classic dominatrix imagery. And you wonder how much of the sexual tortures inflicted on the inmates of Abu Ghraib was inspired by the vast repertory of pornographic imagery available on the Internet -- and which ordinary people, by sending out Webcasts of themselves, try to emulate.

III.

To live is to be photographed, to have a record of one's life, and therefore to go on with one's life oblivious, or claiming to be oblivious, to the camera's nonstop attentions. But to live is also to pose. To act is to share in the community of actions recorded as images. The expression of satisfaction at the acts of torture being inflicted on helpless, trussed, naked victims is only part of the story. There is the deep satisfaction of being photographed, to which one is now more inclined to respond not with a stiff, direct gaze (as in former times) but with glee. The events are in part designed to be photographed. The grin is a grin for the camera. There would be something missing if, after stacking the naked men, you couldn't take a picture of them.

Looking at these photographs, you ask yourself, How can someone grin at the sufferings and humiliation of another human being? Set guard dogs at the genitals and legs of cowering naked prisoners? Force shackled, hooded prisoners to masturbate or simulate oral sex with one another? And you feel naive for asking, since the answer is, self-evidently, People do these things to other people. Rape and pain inflicted on the genitals are among the most common forms of torture. Not just in Nazi concentration camps and in Abu Ghraib when it was run by Saddam Hussein. Americans, too, have done and do them when they are told, or made to feel, that those over whom they have absolute power deserve to be humiliated, tormented. They do them when they are led to believe that the people they are torturing belong to an inferior race or religion. For the meaning of these pictures is not just that these acts were performed, but that their perpetrators apparently had no sense that there was anything wrong in what the pictures show.

Even more appalling, since the pictures were meant to be circulated and seen by many people: it was all fun. And this idea of fun is, alas, more and more -- contrary to what President Bush is telling the world -- part of ''the true nature and heart of America.'' It is hard to measure the increasing acceptance of brutality in American life, but its evidence is everywhere, starting with the video games of killing that are a principal entertainment of boys -- can the video game ''Interrogating the Terrorists'' really be far behind? -- and on to the violence that has become endemic in the group rites of youth on an exuberant kick. Violent crime is down, yet the easy delight taken in violence seems to have grown. From the harsh torments inflicted on incoming students in many American suburban high schools -- depicted in Richard Linklater's 1993 film, ''Dazed and Confused'' -- to the hazing rituals of physical brutality and sexual humiliation in college fraternities and on sports teams, America has become a country in which the fantasies and the practice of violence are seen as good entertainment, fun.

What formerly was segregated as pornography, as the exercise of extreme sadomasochistic longings -- as in Pier Paolo Pasolini's last, near-unwatchable film, ''Salo'' (1975), depicting orgies of torture in the Fascist redoubt in northern Italy at the end of the Mussolini era -- is now being normalized, by some, as high-spirited play or venting. To ''stack naked men'' is like a college fraternity prank, said a caller to Rush Limbaugh and the many millions of Americans who listen to his radio show. Had the caller, one wonders, seen the photographs? No matter. The observation -- or is it the fantasy? -- was on the mark. What may still be capable of shocking some Americans was Limbaugh's response: ''Exactly!'' he exclaimed. ''Exactly my point. This is no different than what happens at the Skull and Bones initiation, and we're going to ruin people's lives over it, and we're going to hamper our military effort, and then we are going to really hammer them because they had a good time.'' ''They'' are the American soldiers, the torturers. And Limbaugh went on: ''You know, these people are being fired at every day. I'm talking about people having a good time, these people. You ever heard of emotional release?''

Shock and awe were what our military promised the Iraqis. And shock and the awful are what these photographs announce to the world that the Americans have delivered: a pattern of criminal behavior in open contempt of international humanitarian conventions. Soldiers now pose, thumbs up, before the atrocities they commit, and send off the pictures to their buddies. Secrets of private life that, formerly, you would have given nearly anything to conceal, you now clamor to be invited on a television show to reveal. What is illustrated by these photographs is as much the culture of shamelessness as the reigning admiration for unapologetic brutality.

IV.

The notion that apologies or professions of ''disgust'' by the president and the secretary of defense are a sufficient response is an insult to one's historical and moral sense. The torture of prisoners is not an aberration. It is a direct consequence of the with-us-or-against-us doctrines of world struggle with which the Bush administration has sought to change, change radically, the international stance of the United States and to recast many domestic institutions and prerogatives. The Bush administration has committed the country to a pseudo-religious doctrine of war, endless war -- for ''the war on terror'' is nothing less than that. Endless war is taken to justify endless incarcerations. Those held in the extralegal American penal empire are ''detainees''; ''prisoners,'' a newly obsolete word, might suggest that they have the rights accorded by international law and the laws of all civilized countries. This endless ''global war on terrorism'' -- into which both the quite justified invasion of Afghanistan and the unwinnable folly in Iraq have been folded by Pentagon decree -- inevitably leads to the demonizing and dehumanizing of anyone declared by the Bush administration to be a possible terrorist: a definition that is not up for debate and is, in fact, usually made in secret.

The charges against most of the people detained in the prisons in Iraq and Afghanistan being nonexistent -- the Red Cross reports that 70 to 90 percent of those being held seem to have committed no crime other than simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time, caught up in some sweep of ''suspects'' -- the principal justification for holding them is ''interrogation.'' Interrogation about what? About anything. Whatever the detainee might know. If interrogation is the point of detaining prisoners indefinitely, then physical coercion, humiliation and torture become inevitable.

Remember: we are not talking about that rarest of cases, the ''ticking time bomb'' situation, which is sometimes used as a limiting case that justifies torture of prisoners who have knowledge of an imminent attack. This is general or nonspecific information-gathering, authorized by American military and civilian administrators to learn more of a shadowy empire of evildoers about whom Americans know virtually nothing, in countries about which they are singularly ignorant: in principle, any information at all might be useful. An interrogation that produced no information (whatever information might consist of) would count as a failure. All the more justification for preparing prisoners to talk. Softening them up, stressing them out -- these are the euphemisms for the bestial practices in American prisons where suspected terrorists are being held. Unfortunately, as Staff Sgt. Ivan (Chip) Frederick noted in his diary, a prisoner can get too stressed out and die. The picture of a man in a body bag with ice on his chest may well be of the man Frederick was describing.

The pictures will not go away. That is the nature of the digital world in which we live. Indeed, it seems they were necessary to get our leaders to acknowledge that they had a problem on their hands. After all, the conclusions of reports compiled by the International Committee of the Red Cross, and other reports by journalists and protests by humanitarian organizations about the atrocious punishments inflicted on ''detainees'' and ''suspected terrorists'' in prisons run by the American military, first in Afghanistan and later in Iraq, have been circulating for more than a year. It seems doubtful that such reports were read by President Bush or Vice President Dick Cheney or Condoleezza Rice or Rumsfeld. Apparently it took the photographs to get their attention, when it became clear they could not be suppressed; it was the photographs that made all this ''real'' to Bush and his associates. Up to then, there had been only words, which are easier to cover up in our age of infinite digital self-reproduction and self-dissemination, and so much easier to forget.

So now the pictures will continue to ''assault'' us -- as many Americans are bound to feel. Will people get used to them? Some Americans are already saying they have seen enough. Not, however, the rest of the world. Endless war: endless stream of photographs. Will editors now debate whether showing more of them, or showing them uncropped (which, with some of the best-known images, like that of a hooded man on a box, gives a different and in some instances more appalling view), would be in ''bad taste'' or too implicitly political? By ''political,'' read: critical of the Bush administration's imperial project. For there can be no doubt that the photographs damage, as Rumsfeld testified, ''the reputation of the honorable men and women of the armed forces who are courageously and responsibly and professionally defending our freedom across the globe.'' This damage -- to our reputation, our image, our success as the lone superpower -- is what the Bush administration principally deplores. How the protection of ''our freedom'' -- the freedom of 5 percent of humanity -- came to require having American soldiers ''across the globe'' is hardly debated by our elected officials.

Already the backlash has begun. Americans are being warned against indulging in an orgy of self-condemnation. The continuing publication of the pictures is being taken by many Americans as suggesting that we do not have the right to defend ourselves: after all, they (the terrorists) started it. They -- Osama bin Laden? Saddam Hussein? what's the difference? -- attacked us first. Senator James Inhofe of Oklahoma, a Republican member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, before which Secretary Rumsfeld testified, avowed that he was sure he was not the only member of the committee ''more outraged by the outrage'' over the photographs than by what the photographs show. ''These prisoners,'' Senator Inhofe explained, ''you know they're not there for traffic violations. If they're in Cellblock 1-A or 1-B, these prisoners, they're murderers, they're terrorists, they're insurgents. Many of them probably have American blood on their hands, and here we're so concerned about the treatment of those individuals.'' It's the fault of ''the media'' which are provoking, and will continue to provoke, further violence against Americans around the world. More Americans will die. Because of these photos.

There is an answer to this charge, of course. Americans are dying not because of the photographs but because of what the photographs reveal to be happening, happening with the complicity of a chain of command -- so Maj. Gen. Antonio Taguba implied, and Pfc. Lynndie England said, and (among others) Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, a Republican, suggested, after he saw the Pentagon's full range of images on May 12. ''Some of it has an elaborate nature to it that makes me very suspicious of whether or not others were directing or encouraging,'' Senator Graham said. Senator Bill Nelson, a Florida Democrat, said that viewing an uncropped version of one photo showing a stack of naked men in a hallway -- a version that revealed how many other soldiers were at the scene, some not even paying attention -- contradicted the Pentagon's assertion that only rogue soldiers were involved. ''Somewhere along the line,'' Senator Nelson said of the torturers, ''they were either told or winked at.'' An attorney for Specialist Charles Graner Jr., who is in the picture, has had his client identify the men in the uncropped version; according to The Wall Street Journal, Graner said that four of the men were military intelligence and one a civilian contractor working with military intelligence.

V.

But the distinction between photograph and reality -- as between spin and policy -- can easily evaporate. And that is what the administration wishes to happen. ''There are a lot more photographs and videos that exist,'' Rumsfeld acknowledged in his testimony. ''If these are released to the public, obviously, it's going to make matters worse.'' Worse for the administration and its programs, presumably, not for those who are the actual -- and potential? -- victims of torture.

The media may self-censor but, as Rumsfeld acknowledged, it's hard to censor soldiers overseas, who don't write letters home, as in the old days, that can be opened by military censors who ink out unacceptable lines. Today's soldiers instead function like tourists, as Rumsfeld put it, ''running around with digital cameras and taking these unbelievable photographs and then passing them off, against the law, to the media, to our surprise.'' The administration's effort to withhold pictures is proceeding along several fronts. Currently, the argument is taking a legalistic turn: now the photographs are classified as evidence in future criminal cases, whose outcome may be prejudiced if they are made public. The Republican chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, John Warner of Virginia, after the May 12 slide show of image after image of sexual humiliation and violence against Iraqi prisoners, said he felt ''very strongly'' that the newer photos ''should not be made public. I feel that it could possibly endanger the men and women of the armed forces as they are serving and at great risk.''

But the real push to limit the accessibility of the photographs will come from the continuing effort to protect the administration and cover up our misrule in Iraq -- to identify ''outrage'' over the photographs with a campaign to undermine American military might and the purposes it currently serves. Just as it was regarded by many as an implicit criticism of the war to show on television photographs of American soldiers who have been killed in the course of the invasion and occupation of Iraq, it will increasingly be thought unpatriotic to disseminate the new photographs and further tarnish the image of America.

After all, we're at war. Endless war. And war is hell, more so than any of the people who got us into this rotten war seem to have expected. In our digital hall of mirrors, the pictures aren't going to go away. Yes, it seems that one picture is worth a thousand words. And even if our leaders choose not to look at them, there will be thousands more snapshots and videos. Unstoppable.

-

"I would say that we had a very close friendship rather than collegial creative collaboration. I don't know why he liked what I was doing."

- (Alexander Sokurov, Film Comment Nov/Dec 1997)

While there is no denying certain similarities of cinematic style between Tarkovsky and Sokurov (such as incredibly long takes, the extremely natural manner of their actors, the poignant use of natural sounds and music - to mention a few), yet there are indeed crucial differences between Sokurov's inner world and Tarkovsky's inner world as these manifest in their films. Both of them are "spiritual" filmmakers in the sense that, in their art they concern themselves with profound questions of human existence and seek to give visible expression to the INNER reality of their being. However, it is precisely in their inner realities that the two could not be more different from each other. In Tarkovsky's films, we see that something is weighing heavily upon the souls of the main characters, something is oppressing their spirits - and yet each film is marked by a phenomenal attempt on the part of the main characters (that is, on the part of the director) to transcend this oppression, to break free from it and to rise above it. Thus, Tarkovsky's cinema is the cinema of striving towards spiritual liberation. In Sokurov's films, we see the opposite. We also observe the oppressed state of the characters - but here, over the course of each film, it becomes increasingly clear that this oppression, this heaviness is something that can not and will not be lifted. The characters make little or no attempt to struggle against this oppression. Instead, Sokurov's cinema is the cinema of and for the expression of this state of spiritual oppression. The case is no different with Sokurov's latest film, Mother and Son , which depicts the final day of an old woman's life as she is being cared for by her son. In this film, the feeling of oppression is everywhere: not only in the faces of the main characters, not only in the claustrophobic, dimly-lit interiors of their house, but in the very air they breathe, in every word they utter. Their speech is slow and heavy (and not just because of the mother's illness), as though even the act of speaking has become an effort for them. Forget speaking - even breathing is an effort for both mother and son, so heavy does their existence weigh upon them! When the son, casting a glance around their outside world, asks the mother: "Well, is it good to live here?" she answers: "Living here is not bad - not bad at all - only it is hard [in Russian, literally 'heavy'] all the time for some reason." This state of heaviness is captured so superbly by Sokurov in every aspect of his film that one is almost not surprised to see even nature cooperating: dark, dense, heavy clouds hang low over the barren landscape throughout the entire film, giving Sokurov's cinematography that "painterly" quality and reinforcing that feeling of oppression. It should be noted in passing, that masterful strokes such as these do not come about as a result of intellectual calculation. Like all great artists, Sokurov works strictly through intuition in his best films. This is invaluable for the seriously seeking viewer, because the director, who works in this way, cannot help but speak the truth through his cinema - as a result, revealing things about himself, of which he may not be fully (or even at all) conscious. Simply put, only he, who is inwardly distorted can create the images of distortion; only he, who is spiritually oppressed, can create the cinema of spiritual oppression. And since in today's world, there isn't ONE among us, who is NOT to some degree inwardly distorted or oppressed, Sokurov's cinema becomes extremely valuable for us - if viewed from this perspective. And where is there in this film even an attempt made to find a connection with the Creator? Where is the striving for a greater meaning in life? When the son implores the mother to go on living, she asks: "What for?" - "What for?" he echoes, "I don't know. As far as I can see, most people live for no particular reason." Mercifully, he doesn't go on to say that she should live for him, though the entire film makes it crystal clear that all they have to live for is each other. There is a critical moment in the film, when the mother is having an attack on the bench outside their house. With her head thrown back, gasping for air, she is looking up at the sky and just at that moment she hears the rolls of thunder: "Who is it up there?!" she cries out in her anguish - for the first and only time in the entire film raising her voice and breaking through this oppressive lethargy, which has enveloped them both. But the son answers in a monotone: "Nobody. There is nobody up there." This is a great illustration of human isolation - isolation from the Light, from Life, from Love, brought about by human beings themselves. Having compressed the concept of true love into narrow and oppressive boundaries of family bonds, human beings now find themselves utterly alone in this world. It is little wonder then that they turn to each other and cling to each other - and this convulsive clinging they now call "love". And when the time comes to leave all that is earthly behind, all they can say, just like the mother does in the film, is: "It's so unfair." The film ends on what some might consider to be a declaration of faith. Sitting near his mother's lifeless body, the son addresses her, saying he knows that she can hear him and telling her to wait for him at the appointed place. Yet one gets the intuitive impression (conveyed through Sokurov's cinematography) that even "over there" there will be no relief for mother and son. She will still be just as weak; he will still be carrying her around everywhere and the world they will live in will still be just as heavy, as oppressed and as dimly-lit. This intuition is indeed accurate, because under the Natural Order of this Creation there can be no change in the circumstances of any individual until there is an INNER CHANGE OF PERCEPTION. This simple process holds true for ALL levels of our existence - therefore, it is just as applicable AFTER earthly death as it is in our present earthly life. The connection with the Light cannot be re-established unless every son and every mother and every daughter and every father recognizes the necessity to direct their gaze BEYOND family relationships and to acquire the Knowledge enabling everyone to place family relationships into a proper perspective within the workings of Creation. This Knowledge is now available to everyone through the book "In the Light of Truth: the Grail Message" by Abd-ru-shin. At one point in the film, mother and son are sitting in the tall grass and the son says: "Creation - it is wonderful." The searing contrast between these words and his oppressed expression creates quite a dissonance. Is there, perhaps, a regret in his voice that the two of them remain cut off from the wonder of Creation? Is there a longing deep within him to still find a way back to that wonder? Mother and Son is the most powerful record on film up to date of the oppressed state of the human spirit. And Sokurov is a truly contemporary film artist. He is the voice of the people - and not only of the Russian people, as he seems to think, but of spiritually oppressed people everywhere - because through his cinema he intuitively expresses the condition of their souls: no longer striving for anything, they exist "for no particular reason", barely able to move under the pressure of their own false conceptions.

- "We shouldn't be afraid of difficult films, we shouldn't be afraid not to be entertained. The viewer pays a high price for a film. And not in money. Viewers spend their time, a piece of their lives – an hour and a half to two hours. A bad film, an aggressive film, takes several centuries of life from humanity. " (Alexander Sokurov)

-

The soft amber glow of that magic moment when summer fire dissipates into the smoldering whispers of autumn. The nostalghia for a time and place long forgotten where the light never ends and dreams linger like stardust in the hallways and byways of an ancient golden city. The longing for a true brotherhood, where there are no base thoughts or deeds, only a pure spiritual understanding between individuals. These are all fleeting impressions, which one gathers like flint to a brush while watching the controversial masterpiece, "Father and Son", by the renown Russian auteur Alexander Sokurov. Mind you, these are only flittering little waves that reached the hearts of these reviewers and may or may not have been the intention of the filmmaker. And there are some other things in this film that unfortunately run counter to these impressions.

But what makes a Sokurov-experience different from that of any other director is his sheer power and mastery in transmitting his inner spiritual world onto the silver screen. Only a handful of directors in cinema history have managed to successfully create a spiritual experience inside the film itself, chief among them is Sokurov's mentor Andrei Tarkovsky, the Armenian Sergei Paradjanov, Robert Bresson, Godfrey Reggio and Ingmar Bergman. All of their (and Sokurov's) greatest work remind us that the fecundity of cinema exists to bring people back in touch with the world of their spirits and not their self-serving intellects. Cinema is not here to amuse us or to distract us from our earthly burdens through an onslaught of depravity or nonsensical tomfoolery. At its best, cinema offers us an uncanny x-ray of our spiritual inner beings. It reminds us that the world we live in is, at the moment, completely removed from the world of our spirits. This naturally brings up the unsettling question: what then has given rise to the dichotomy between these two worlds? Shouldn't they be one and the same? Did not mankind receive in the Lord's Prayer the words: "Thy Kingdom come, Thy will be done, on Earth as it is in Heaven?" What then has lead to this grave disparity, this turning away from the life of the spirit?

If there is one achievement Alexander Sokurov should be remembered for in the annals of great artistic accomplishments, it is his relentless striving to bring the world of the spirit closer to our own. With the exceptions of Tarkovsky and Bresson, there has never been a director who places such an emphasis on the spiritual qualities of harmony, subtlety and refinement in all aspects of the filmmaking process (and in life as well):

"Artistic people are mostly chaotic, and sometimes there's destructiveness, at least that's what I saw. There's more chaotic personalities among contemporary people. This means they never worked seriously on themselves, they hate it, and will never do it. Most artists don't tend to harmony. They're not delicate, because they achieve harmony neither in art nor in life. That's the big problem for contemporary artists, for the so called creative part of the literate people....Artistic persons by their nature don't seek harmony, and this is a big problem with contemporary art. The main rule of classical art, that grounds all art, is the pursuit of harmony. Contemporary artists have forgotten this main law, and this is a road to nowhere, a dead-end without future. If you don't seek harmony then you quickly get some result. An artist can not achieve the result in his lifetime. The more he grows in art, the farther it steps from him, as if provoking 'Come on, create more, make more, go on, don't stop.'" (Alexander Sokurov, Sputnik)

In a perfect world, of course, art (and the artist) would not be separated from spiritual life. They would ebb and flow together in a Light-conscious stream, uplifting the surrounding world as a natural matter of course. For art is life, and life is art. We are all part of the great Work of Creation, which is the sacred model for all Art. And as long as the pure flame of the spirit is firmly in command, this marvelous balance can be striven for, maybe even achieved. The moment, however, the spirit weakens, as is the case with most filmmakers today, then the inevitable maelstrom follows:

"Only the works of the spirit from their very origin bear life within them, and with it permanence and stability. Everything else must collapse from within when its time of blossoming is past. As soon as the fruits of it are due to appear, the barrenness will be exposed!

"Just look at history! Only the work of the spirit, that is to say art, has outlived the peoples who have already collapsed through the activity of their intellect, which in itself is lifeless and cold. Their great, much-praised knowledge could not offer them any salvation from collapse. Egyptians, Greeks and Romans went this way; later also the Spaniards and the French, now the Germans - yet the works of genuine art have outlived them all! Nor can they ever perish." (Abd-ru-shin, In the Light of Truth: The Grail Message, Ch.19, Vol.1)

- "Oriental Elegy", "A Humble Life", "Spiritual Voices, Part 1", "Mother and Son" and "Father and Son" are all fairly recent films in Sokurov's canon. And eventhough they each have their own temperament, they share a common yearning to eschew the cruelty of death and attain safe passage into eternal life, hence they are often filled with incredibly expansive lengths of time between cuts. (Of course, his most famous film, "Russian Ark, is well-known for its single take, but we have chosen to exclude this film because of its more superficial nature.) In this way, Sokurov has taken Tarkovsky's philosophy of "sculpting in time" to an extreme not even the great Russian master could have imagined. But these expanses should not be measured just in terms of the clock. Sometimes, as in the case of "Father and Son", short passages can also linger in a state of timelessness, filled with deep inner feeling. For example, the dream sequences, which open and close the film. Also, the marvelous montage-interplay between the son and his girlfriend, as well as the trip the two young men take through the glowing streets of the golden city. Sokurov also uses distorted lenses for the city sequence and this seems to add to the effect of transcendence - he used this technique before in "Mother and Son" to astonishing effect.

So what exactly does Sokurov do in these eternal expanses? Sokurov is consistently able in these films to discover subtle, deeply mysterious images that resonate profoundly in the open spaces he provides for them: "I was always driven by visual aesthetics, aesthetics which connected to the spirituality of man, and set certain morals." (Alexander Sokurov, Film Comment) For example, "Oriental Elegy" begins with a haunting mist that remains throughout the entire film. Through the mist, trees appear and then, as the camera pans, we see that we are on an island. The silhouette of the director is cast before a glowing moonlit lake. On the soundtrack we hear the Sokurov's voice, sounding alone and fascinated by this world within a world within a world. The mist carries us to a hillside covered with ancient buildings. A weathered statue of the Buddha appears and disappears. We hear in the far off distance snippets of Wagner and Japanese folksongs and the desolate sounds of wind and birds. Soon we are inside a modest Japanese home. The mist seeps through the doors and windows. We encounter a woman. Is she a ghost? Perhaps a floating memory of the distant past suspended like a dangling leaf in the unearthly fog? The mist carries us onwards, revealing more and more of its secrets. On this lost night, we are the ghosts searching for what we have lost. Only the mist knows us, and we are its captives. The whole film seems like one long take, eventhough it is quite segmented. This is surely one of the most beautiful films ever made.

On the other hand, it must be admitted that not all of Sokurov's images are up to the challenge of representing the spirituality of man, especially in "Father and Son". In fact, some of his "visual aesthetics" in this film are so askew from the world of the spirit that they often leave us in a state of complete bewilderment. Why, for instance, both father and son have such pumped-up, muscular bodies, which they continuously display by walking around bare-chested? This certainly doesn't help the viewer to make an immediate association with the spirituality of their relationship, which, after all, is at the very core of this film. Also, such overt display of physicality is highly unusual in Sokurov's work: most of his male characters have a normal physique of a person, who is more preoccupied with his inner life than with the sculpting of his muscles. Why then a change in this film of all films, a film that deals specifically with spirituality among men?.. Such strange choice of new physical aesthetics (new for Sokurov) has had far graver consequences for the director than he might have realized at first. It has created confusion in the viewers' associations, prompting one critic to call this one of the most homo-erotic straight films ever made. Sokurov, for his part, gets justifiably upset, when his film is reduced to a homo-erotic interpretation:

"Don't try to put your own complexes onto the movie. Let it live! Be kind! Homo-erotic? For the movie you have seen, there's no such low meaning. In a cruel world, nothing can be accepted but a homo-erotic view. I don't see a place for it. I'm not interested in discussing it." (Alexander Sokurov)

It has, unfortunately, become an accepted practice to view not only all art, but even all life from a sexual perspective. Yet a genuine artist, as well as any intuitive person, will always have a natural aversion to this type of reduction. The New Time will be defined by the complete spiritualization of humanity - and this most definitely includes the area of sexual practices. They are not to be pushed aside, but thoroughly incorporated into the spiritualizing process, which quite naturally implies that sex can only take place under the conditions of genuine and profound spiritual love. Perhaps, this would be a good time to clarify for ourselves what constitutes the actual essence of man and what distinguishes him before all other creatures: his spirit.

"...I want to explain what spirit, as the only living part in man, is. Spirit is not wit, and not intellect! Nor is spirit acquired knowledge. It is erroneous, therefore, to call a person "rich in spirit" because he has studied, read and observed much and knows how to converse well about it, or because his brilliance expresses itself through original ideas and intellectual wit."Spirit is something entirely different. It is an independent consistency, coming from the world of its homogeneous species, which is different from the part to which the earth and thus the physical body belong. The spiritual world lies higher, it forms the upper and lightest part of Creation. Owing to its consistency, this spiritual part in man bears within it the task of returning to the Spiritual Realm, as soon as all the material coverings have been severed from it. The urge to do so is set free at a very definite degree of maturity, and then leads the spirit upwards to its homogeneous species, through whose power of attraction it is raised."Spirit has nothing to do with the earthly intellect, only with the quality which is described as "deep inner feeling" ("Gemuet"). To be rich in spirit, therefore, is the same as "having deep inner feelings" ("gemuetvoll" ), but not the same as being highly intellectual. " (Abd-ru-shin, In the Light of Truth: The Grail Message, Ch.19, Vol.1)

-

It quite naturally follows that man has a duty (a sacred duty, one might say) to see to it that the spiritual core, with which he has been endowed by his Creator, is not smothered by the baser tendencies of the material world. This in no way implies abstinence from material activities, but the most purposeful spiritualization of all of these activities. And Sokurov's primary concern is most definitely with the spiritualization of humanity. Where he goes wrong, however, is in advocating family relationships as the solution to the rapidly declining spirituality and morality in the world:

"Relations of blood are eternal... To try to distance yourself from your father should be a crime... there is no other object here than improving the morals, making us kinder." (Alexander Sokurov on "Father and Son")

It is an urgent necessity for anyone, who wishes to help arrest the spiritual and moral decline of humanity, to familiarize yourself first with the Eternal Laws of this Creation, because only from the perspective of these Laws can one gain some understanding of the Eternal Principles that match children to their particular parents. Then words, like "eternal", would not be misused, for the relations of blood in particular are NOT eternal. (Read " THE MYSTERY OF BIRTH" by Abd-ru-shin from "In the Light of Truth: The Grail Message".) While Sokurov has nothing but the best intentions at heart in wishing to help humanity, what he ends up doing is installing family relations on such a high pedestal as to make an idol out of them, thus violating the First Commandment, which warns against all idolatry. ( Read an illuminating explanation of The First Commandment.) Another problem with Sokurov's assertion that trying "to distance yourself from your father should be a crime" is that in some cases, under the Laws of this Creation, distancing yourself from your father or your mother may be the right thing to do precisely for spiritual reasons. Those, who at one point or another have suffered in a family situation and struggled desperately (but in vain) to uphold the Commandment "Thou Shalt Honor Father and Mother!" will want to read Abd-ru-shin's explanation of it.

In short, family relations are not automatically spiritual in and of themselves. Certainly, it is a worthy goal to try to transform them into truly spiritual relationships, but where this is not possible, they should not be prolonged by a kind of clinging to each other. There must at all times prevail a clear understanding that a child is an already formed and independent human spirit, who can inherit nothing of spirituality from its parents, but who must continue to develop its own spirituality.

- Sokurov's passionate advocacy of family closeness as the way to spirituality and upliftment of humanity is not in harmony with the Laws of Creation, since in most cases, the family provides comfort, but no real basis for spiritual develop-ment. However, one should be careful not to lay blame for this squarely on Sokurov's shoulders. This is a worldwide frailty that has infected each and every one of us. Sokurov leaves himself open for criticism only because he is working at such a high spiritual level that his distortions glare evermore brazenly back at us. If he were a mediocre filmmaker, nobody would even notice. Heck, he probably would even win an Oscar. But such is the fate of the extremely gifted. They are at the forefront of humanity, so they are the ones that get poked and prodded and plundered first. That said, never for one moment in these selected films is there the slightest hint of falsehood. On the contrary, even with such distorted efforts as "Mother and Son" and especially "Father and Son", Sokurov's genuineness and sincerity more often than not seem to win through, which indicates that this is an artist of exceptional spiritual acuity and wakefulness.

In "Father and Son" he creates such a sustained spiritual atmosphere that Biblical references seem quite unnecessary, even unnatural. One such reference is repeated throughout the film: "A father's love crucifies; a son's love lets itself be crucified." It sounds somewhat poetic, but what does it actually mean?.. Humanity as of yet has not become clear on the real meaning of the crucifixion of Christ, and yet parallels with human relationships are already being drawn. (To discover the true meaning of Christ's crucifixion, read " The Crucifixion of the Son of God and the Lord's Supper" by Abd-ru-shin.)

-

"... conflicts arise when debts are not paid to our parents." (Alexander Sokurov)

-

Our first filial duty is to God the Father, Whose spiritual children we are. It is by no means to be assumed that our earthly parents live in harmony with His Will and His Laws. For this reason it is necessary to re-examine everything we have learned from our parents, comparing it objectively and courageously with the Light of Truth that has been sent into Creation at this time of purification. The Word has been sent to us for the second time since Jesus, because we have proved to be utterly incapable of grasping It in the form, which Jesus gave It during His stay on earth two thousand years ago. Naturally, the Word Itself remains the same for all eternity, but a Divine Envoy always gives It that form, which corresponds to the maturity level of humanity at a given time. Thus, for our time, the Word has been given the form which is suited to our highly intellectual way of thinking and which addresses our numerous distortions of basic concepts, such as Love, Justice, Purity, freedom, family etc. Those with an alert spirit and an objective mind will find It in "IN THE LIGHT OF TRUTH: THE GRAIL MESSAGE" by Abd-ru-shin (original in German "IM LICHTE DER WAHRHEIT: GRALSBOTSCHAFT")

苏珊 桑塔格-1990年代10部最佳电影

There's no director active today whose films I admire as much. The Days of Eclipse (1988) is, I think, his greatest film.

【第二圈——亚历山大·索科洛夫——1990——俄罗斯】

2. Close Up (Abbas Kiarostami, 1990)

Iranian cinema has been the great revelation of the last decade. Close Up is my (and, I've heard, Kiarostami's) favorite of his films.

【特写——阿巴斯·基亚罗斯塔米——1990——伊朗】

3. The Stone (Aleksandr Sokurov, 1992)

Chekhov's ghost features in this film meditation about a night at Yalta's Chekhov Museum.

【石头——亚历山大·索科洛夫——1992——俄罗斯】

4. Naked (Mike Leigh, 1993)

I've been a Mike Leigh fan since 1977's Abigail's Party (as good as Moliere). Naked is, I suppose, his deepest film.

【赤裸——迈克·李——1993——英国】

5. The Puppetmaster (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1993)

Set in the '30s and '40s. The Taiwanese director is just as marvelous as everyone says.

【戏梦人生——候孝贤——1993——中国台湾】

6. Satantango (Bela Tarr, 1994)

Devastating, enthralling for every minute of its seven hours. I'd be glad to see it every year for the rest of my life.

【撒旦探戈——贝拉·塔尔——1994——匈牙利】

7. Lamerica (Gianni Amelio, 1994)

Epic, "realistic," true--a great, moral film, and perhaps the saddest film I've ever seen.

【亚美利加——乔瓦尼·阿美利奥——1994——意大利】

8. Joan the Maid (Jacques Rivette, 1994)

A masterpiece. Rivette, alone among the great filmmakers of his generation, has not changed or lowered his sights. Sandrine Bonnaire isn't Falconetti, but she is Joan of Arc.

【圣女贞德——雅克·里维特——1994——法国】

9. Through the Olive Trees (Abbas Kiarostami, 1994)

Brilliantly made, irresistibly touching.

【橄榄树下的情人——阿巴斯·基亚罗斯塔米——1994——伊朗】

10. Goodbye South, Goodbye (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1996)

Hoodlum-losers in the new Taiwan. As amazing as his stately, subtle, beautiful Flowers of Shanghai (1998), set in the 1880s.

【南国再见,南国——候孝贤——1996——中国台湾】

The Best Films of the 1990s

Ten Years of Sitting in the Dark

By Jeffrey M. Anderson

When I was working for Bayinsider, I was a bit rushed to get in my list of the ten best films of the 1990's by December 31, 1999. I regret the list I posted there now, and I think now that the smoke has cleared, I ought to post a more definitive list. Here's what I came up with now that I've had time to really think it over.